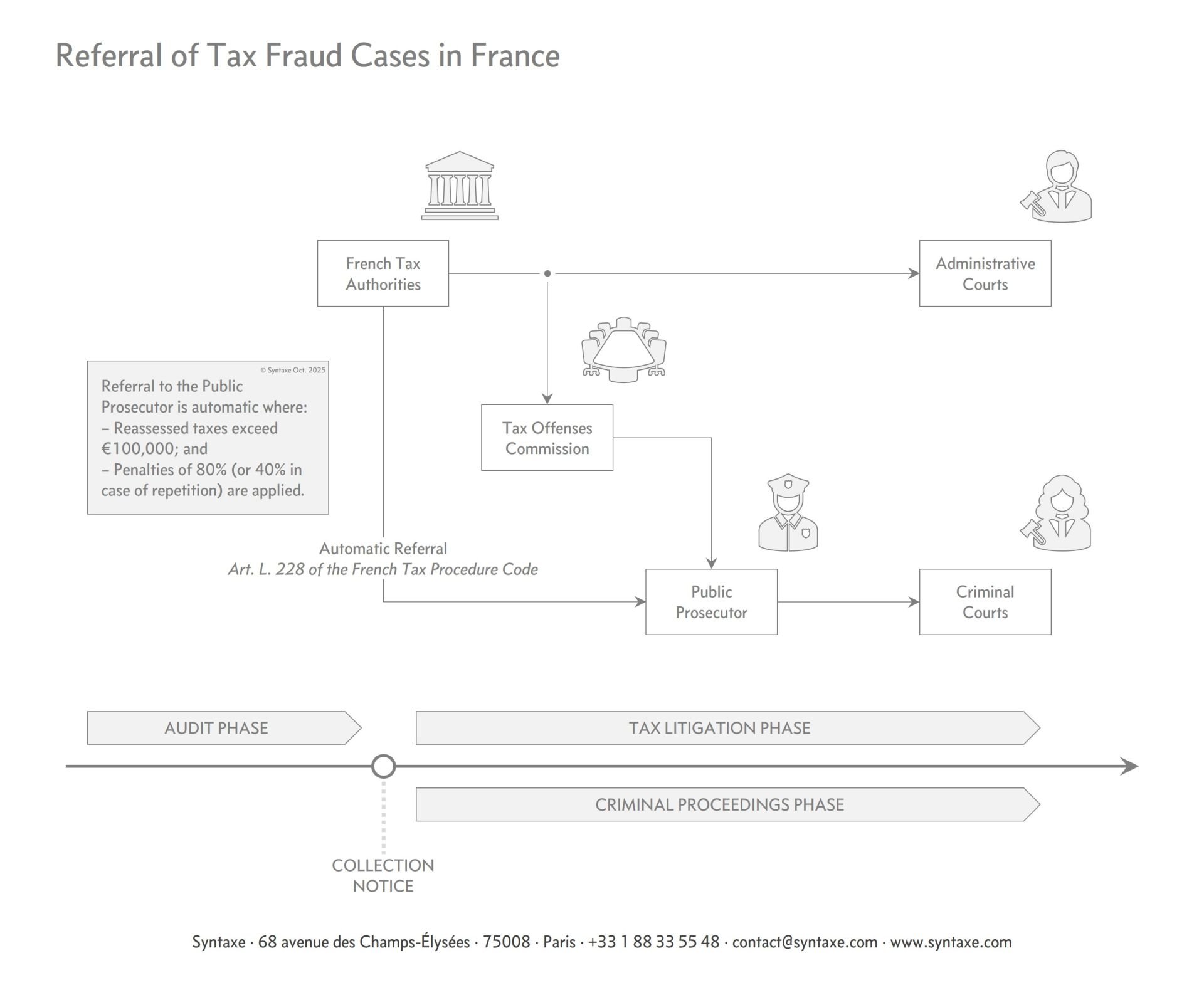

Since the 2018 Anti-Fraud Law, French tax audits can automatically turn into criminal cases. When total reassessed taxes exceed €100,000 and an 80% (or repeated 40%) penalty applies, the case must be referred to the public prosecutor under Article L. 228 of the French Tax Procedure Code. The referral is automatic and irreversible. Administrative and criminal proceedings then run in parallel, often with limited coordination between authorities. The decisive stage is therefore the audit: the penalties chosen by the French Tax Authorities determine whether criminal prosecution will follow.

In the French tax system, the boundary between administrative reassessment and criminal prosecution has become increasingly thin. Since the 2018 Anti-Fraud Law[1], certain reassessments must now be automatically referred to the public prosecutor in addition to the tax procedure. What once remained an administrative matter can, under the same set of facts, now evolve into a criminal case.

The Move to Automatic Referral

For many years, criminal prosecution for tax fraud (fraude fiscale) in France was subject to a safeguard mechanism.

In the course of a tax audit, the French Tax Authorities had to refer a case to the Tax Offenses Commission (Commission des Infractions Fiscales or CIF) before any criminal proceedings could be initiated. The Tax Offenses Commission assessed both the legal grounds for referral and the merits of prosecution in light of the facts and circumstances of the case.

Such a referral subjected the taxpayer to the full force of both tax and criminal proceedings. In practice, the French Tax Authorities reserved this ordeal for the most serious fraud cases, when they wanted to make an example of the taxpayer.

This filter has since been partially lifted. The 2018 Anti-Fraud Law introduced a system of automatic referral to the public prosecutor (dénonciation obligatoire au parquet) whenever certain thresholds are met, without any prior review by the Tax Offenses Commission.

Since its entry into force, the number of cases referred to the public prosecutor (whether through the Tax Offenses Commission or by automatic referral) has roughly doubled and continues on an upward trend, as shown below.[2] They now concern not only large-scale, sophisticated fraud but also smaller, more ordinary cases where the cumulative amount of reassessed taxes easily exceeds the €100,000 threshold.

|

Year |

Automatic referrals | Referrals via the Tax Offenses Commission | Cases referred to the “Tax Police” | Escroquerie cases |

Total referrals for criminal prosecution |

|

2016 |

N/A | 862 | 81 | 133 | 1,076 |

|

2017 |

N/A |

879 | 44 | 141 |

1,064 |

|

2018 |

N/A |

806 | 10 | 119 |

935 |

|

2019 |

965 |

672 | 41 | 127 | 1,805 |

|

2020 |

823 |

408 | 41 | 212 | 1,484 |

|

2021 |

1,217 |

286 | 45 | 72 |

1,620 |

|

2022 |

1,373 | 257 | 48 | 92 |

1,770 |

|

2023 |

1,444 | 268 | 42 | 135 |

1,889 |

|

2024 |

1,695 | 314 | 31 | 136 |

2,176 |

Conditions for Automatic Referral

Under Article L. 228 of the French Tax Procedure Code, two cumulative conditions trigger the automatic referral mechanism:

- the total amount of taxes reassessed exceeds €100,000; and

- the reassessment carries a penalty of at least 80% (or 40% in cases of repeated offense).

In practice, situations involving undeclared foreign accounts, life insurance policies, crypto assets, or trusts are particularly exposed, since these situations systematically trigger 80% penalties.

A €100,000 Reassessment Threshold

The first condition is quantitative. The amount of taxes reassessed must exceed €100,000 (or €50,000 for public officials).

Importantly, this threshold is global, not annual. It applies across all taxes and all years covered by the reassessment: income tax, corporate tax, VAT, wealth tax, inheritance tax, and others.

Given the standard three-year audit window, this threshold is reached more often than expected. Many taxpayers are caught off guard when they discover that the aggregate reassessment, not the annual amount, determines whether the case will be transmitted.

An 80% Penalty (or 40% in Case of Repetition)

The second condition concerns the severity of penalties applied.

French tax law provides an extensive range of administrative penalties, calculated as a percentage of the additional taxes reassessed. Depending on the gravity of the taxpayer’s conduct, these penalties range from 5% for minor infractions to 100% for obstruction. There is no official classification, but in practice we generally observe the following scale:

- between 5% and 20% for simple errors or negligence;

- 40% to 50% for serious breaches;

- 80% to 100% for fraudulent or obstructive behavior.

However, this categorization is not always consistent. Certain reporting failures, such as undeclared foreign assets or trusts, automatically fall within the 80% category, even in the absence of proven fraudulent intent.

Automatic referral applies when the French Tax Authorities impose any of the following administrative penalties:

- a 100% penalty for obstruction to tax audit (opposition à contrôle fiscal);[3]

- an 80% penalty for:

- concealed business (activité occulte);[4]

- misuse of law (abus de droit);[5]

- fraudulent tactics (manœuvres frauduleuses);[6]

- failure to comply with foreign bank accounts or life insurance policies disclosure;[7]

- failure to declare crypto assets;[8]

- failure to comply with trust reporting obligations;[9]

- a 40% penalty, but only when similar conduct has been repeated within the previous six years, for:

Given how broadly these categories are defined, many reassessments now fall within the automatic referral zone.

In practice, this second condition depends entirely on the discretion of the French Tax Authorities in qualifying a taxpayer’s behavior and selecting the corresponding penalty rate. This choice can later be challenged before the administrative courts, but at the time of assessment, it determines whether the case will fall under the automatic referral regime.

For instance, the distinction between misuse of law (80%) and deliberate negligence (40%) often lies in a grey area rather than in clear evidence. Much depends on how the authorities interpret the facts, and reasonable arguments can often be made either way. A significant part of the defense work at this stage involves contesting that qualification, with an 80% penalty sometimes successfully downgraded to 40%, 10%, or even removed altogether. The issue is that the automatic referral mechanism does not wait for this debate to be settled: once the French Tax Authorities apply a qualifying penalty, the case must be transmitted to the public prosecutor, even if the penalty is later reduced or cancelled.

What Happens After the Referral

When these two conditions are met, the referral to the public prosecutor becomes mandatory. The French Tax Authorities has no discretion.

Transmission occurs at the stage of the formal collection notice (avis de mise en recouvrement), i.e. once the audit is closed and the reassessment finalized, but before any review by the administrative courts. From that point, no adjustment or settlement can prevent referral. The public prosecutor then decides whether to pursue, though in practice prosecution almost always follows.

When thresholds are not met, the French Tax Authorities may still refer a case to the Tax Offenses Commission for potential prosecution under the traditional system.

Criminal proceedings unfold independently from the tax litigation process. Taxpayers and their advisers must therefore prepare for a dual front, managing both the administrative procedure and the criminal defense in parallel.

In theory, both proceedings share the same underlying facts. In practice, they often evolve separately, with limited coordination between the administrative and criminal sides. Each authority retains its own interpretation, and divergent outcomes are not rare.

We once faced a case where the French Tax Authorities had registered a lien (hypothèque) on a taxpayer’s property to secure payment of the reassessment, while the public prosecutor simultaneously obtained another guarantee on the very same asset to secure potential criminal fines. The result was a bureaucratic absurdity: the State arguing against itself in court, with each branch competing to collect its own share.

The Narrow Exception: “Spontaneous” Correction

There is one exception: spontaneous correction (régularisation spontanée).

In theory, a taxpayer who voluntarily corrects an omission before any audit or inquiry can escape the automatic transmission to the public prosecutor.

In practice, however, the French Tax Authorities interpret spontaneity very narrowly: a correction ceases to be “spontaneous” as soon as any form of audit or inquiry has begun.

The notion extends broadly: an audit notice (avis de vérification), a reassessment notice (proposition de rectification), or even a simple request for information (demande de renseignements) is deemed enough, in the eyes of the French Tax Authorities, to strip a declaration of its spontaneous nature. From that moment, any rectification, even if full and cooperative, is treated as part of the audit and may trigger automatic referral, if the conditions are met.

Criminal Sanctions Incurred

The criminal offense of tax fraud (fraude fiscale), defined under Article 1741 of the French Tax Code, covers any intentional act or omission designed to evade or attempt to evade taxation.

The means commonly cited include:

- failing to file a tax return;

- concealing taxable income or assets;

- falsifying accounting records;

- organizing insolvency;

- using artificial structures or false documents to mislead the French Tax Authorities.

The decisive element is the intent to defraud (intention frauduleuse). In theory, it must be proven by the prosecution; in practice, the bar for establishing it is low.

From what we see in criminal tax cases, courts tend to infer fraudulent intent from patterns of behavior: uncooperative conduct, repeated omissions, or simply the scale of reassessed taxes. In some situations, a single failure to file is enough to convict.

When a case is automatically referred, the presence of an 80% penalty (or repeated 40% penalties) is often seen as a strong indication of deliberate behavior, which significantly narrows the defense margin.

Conviction for fraude fiscale may result in:

- Up to five years of imprisonment and a €500,000 fine (or twice the amount of tax evaded).

- Up to seven years of imprisonment and a €3 million fine in cases with aggravating circumstances, such as the use of foreign accounts, interposed entities, false identities, or fictitious domiciliation abroad.

- For legal entities, fines can reach five times the above amounts.

Complementary sanctions include:

- publication of the judgement;

- exclusion from public procurement;

- disqualification from professional practice;

- suspension of civic and family rights.

Criminal and administrative sanctions are applied cumulatively. Case law allows such cumulation but caps the total amount of fines at the highest ceiling provided either by tax law or by criminal law.

Why the Audit Phase Is Decisive

What once passed through an administrative filter now rests on simple arithmetic: if back taxes exceed €100,000 and penalties of 80% (or 40% in case of repetition) apply, the case is transmitted to the public prosecutor, automatically.

For taxpayers and their advisers, this makes the audit phase absolutely decisive. The penalties applied by the French Tax Authorities at the reassessment stage effectively decide whether criminal proceedings will be triggered. Once the avis de mise en recouvrement is issued with qualifying penalties, the referral becomes automatic and irreversible.

Even if those penalties are later reduced or canceled during litigation, or if the reassessed taxes fall below the €100,000 threshold, the horse has already bolted: the criminal case follows its own path, independently from the administrative proceedings.

In practice, this means that exposure must be identified and managed before the reassessment becomes final. Negotiating penalty levels, documenting good faith, and engaging with the French Tax Authorities early are often the most effective ways to prevent a case from moving into criminal territory.

References

[1] Law No. 2018-898 of 23 October 2018 – Légifrance

[2] Excluding (i) proceedings for criminal obstruction of tax officials in the course of their duties (opposition à fonctions, Article 1746 of the French Tax Code) and (ii) cases relating to fraud involving the Covid-19 solidarity fund.

[3] Article 1732 of the French Tax Code

[4] Article 1728, 1, c of the French Tax Code

[5] Article 1729, b of the French Tax Code

[6] Article 1729, c of the French Tax Code

[7] Article 1729-0 A of the French Tax Code

[8] Article 1729-0 A of the French Tax Code

[9] Article 1729-0 A of the French Tax Code

[10] Article 1728, 1, b of the French Tax Code

[11] Article 1729, 1, a of the French Tax Code

[12] Article 1729, 1, b of the French Tax Code